Masscult and Midcult Revisited

Dwight Macdonald (ed. by John Summers)

Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain

New York: New York Review Books, 2011

Long before Paul Fussell’s Class, or Jilly Cooper’s Class, or such dubious offerings of social criticism as The Preppy Handbook and The Yuppie Handbook, we had Dwight Macdonald’s Masscult and Midcult, a long essay originally written for the Partisan Review and published as a slight volume in 1961. More recently (2011) it was republished as a New York Review Books (NYRB) Classics title, bound together with an Introduction by Louis Menand and a collection of pointed and frothy Macdonald writings from the same era, originally published as Against the American Grain.

If Masscult and Midcult (hereinafter M&M) does not stick in popular memory like Fussell’s Class, it’s probably because it doesn’t have any cartoons or other illustrations. There are funny bits, to be sure (such as his description of Life magazine; see below), because Macdonald was a funny guy himself and appreciated snarky wit in others. One of his best books, assembled around the time he was writing M&M, is his fat collection Parodies (1960). If Macdonald had been like Fussell and written M&M as an openly biased, satirical denunciation of trends he didn’t like in modern culture — and perhaps dressed it up with some satirical drawings by Charles Addams or Robert Osborn? — he might have produced a comic classic, indeed. Unfortunately here he is in dead earnest, valiantly pushing on a string as he struggles to explain his Great Unifying Theory of art and culture.

Dwight Macdonald had once aspired to be a Marxian or socialist political theorist, but unlike his friends James Burnham and George Orwell (for a few years they were all writing for Partisan Review, where Macdonald was an editor from 1937 until 1943), he never completely shook himself free of that ambition. And so, when he drafted M&M in 1960, he hitched himself back into the traces of an old and familiar ideology. He’d been refining a pet theory over and over again since the 1930s. It went sort of like: There is High Art and there is Low Art. Once our Low Art was mainly folk art (not many examples at hand, though he does mention the poetry of Robert Burns), but that’s gone by the wayside, thanks to mass production and universal literacy and all that. For the last couple hundred years, Low Art has increasingly consisted of manufactured kitsch. That includes most movies, drama, fiction, music, popular periodicals, etc., even though some of these may have aspirations for something finer, thus producing pretentious art that is neither High nor Low. Middlebrow entertainment, in other words: the Midcult. That need to seem profound and highbrow is one of Midcult’s earmarks, but such ambition tends to be thwarted by the other Midcult characteristic: Instead of actively engaging our intellect and emotions, Midcult tells us what we should be thinking and feeling.

Macdonald’s classic example of Midcult drama is Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, with its folksy Stage Manager who not only explains the action on stage, but lets us know how to react to it. (Macdonald liked Wilder, and thought this cornpone, Norman Rockwellish play was a wonderfully ironic joke at the expense of Midcult rubes.) Other Midcult examples are late-career Ernest Hemingway (The Old Man and the Sea takes a particular lashing), Stephen Vincent Benet’s John Brown’s Body, and Oscar Hammerstein II’s vapid, unctuous lyrics in Oklahoma and South Pacific. Macdonald belongs to that legion of Broadway-song connoisseurs who regard Rodgers & Hart as True Art, while ritually despising Rodgers & Hammerstein. He ridicules a New York Times obituary praising Hammerstein’s maudlin lyrics, noting that the paper had barely noticed when Larry Hart passed on many years earlier.

As a theory the Masscult/Midcult thing is gossamer-thin, and not equal to the freight Macdonald wants to load into it. But that’s all right, because Macdonald wasn’t a philosopher, he was a scribbler, a captious critic observing the passing scene. Paradoxically he was himself the Midcult Man incarnate. Workaday journalism and reviews: that’s where he shone. The one really lasting effect Macdonald had on big-think cultural criticism was a short-term success and arguably a long-term disaster. In the late 1930s he encouraged a neophyte critic named Clement Greenberg to write art criticism for Partisan Review, and to promote avant-garde painting — that is, painting that wasn’t about people or trees, but about painting: what would soon become known as Abstract Expressionism. As it was unique, unfamiliar, and inimical to mass production, this was to become the preferred high-culture form of painterly art. Greenberg, and Partisan Review, set about this task with a will, beginning in 1939 with “Avant-garde and Kitsch.” In that essay we find enunciated most of the notions that Dwight Macdonald would later rework, in friendlier prose, for Masscult and Midcult.

You can buy H. L. Mencken’s The Passing of a Profit and Other Forgotten Stories here.

In 1951, many years after leaving Luce and Fortune, Macdonald went to work at The New Yorker. For years, sneering at the Time-Fortune-Life combine and H. R. Luce the “baby tycoon” (Harold Ross’s phrase) was very much the done thing at The New Yorker. Back at Partisan Review he knew the difference between Avant-garde and Kitsch, between High Art and Masscult. But The New Yorker might be where Macdonald first formulated his notion of “Midcult,” exemplified by magazines that thought they were aimed at smart, modern, aware people, but were really just pandering to that audience and flattering their prejudices. Like Time, you know.[1]

Now, an obvious irony here is that Macdonald’s beloved New Yorker itself was and is the preeminent Midcult periodical, far more than Time, which was basically just a weekly newspaper which, like all newspapers, have clear editorial biases. But The New Yorker was positioned as something different, not a mere provider of news and entertainment. It was a prosperous rag that survived in style by running advertisements of upscale hats and shoes and eateries, advertisements that were themselves a big draw, all tastefully separated from each other by grey text-blocks of bien-pensant opinion and froth . . . opinion and froth that managed never to challenge the magazine’s very narrow, self-imposed version of the Overton window.

To the young Tom Wolfe this was the funniest thing about The New Yorker. He earned Macdonald’s everlasting wrath by ridiculing The New Yorker‘s Midcultiness, something Macdonald recognized but did not like to admit, because of his loyalty to the magazine and especially to its editor, William Shawn. But we’ll come to that shortly.

He had no such ambiguity in his attitude toward Life, the vast picture magazine launched by Luce in 1936, which seemed to go so far down the Masscult road that Macdonald took it to be it as emblematic of the whole Masscult style:

Its contents are as thoroughly homogenized as its circulation. The same issue will present a serious exposition of atomic energy followed by a disquisition on Rita Hayworth’s love life; photos of starving children picking garbage in Calcutta and of sleek models wearing adhesive brassières; an editorial hailing Bertrand Russell’s eightieth birthday (A GREAT MIND IS STILL ANNOYING AND ADORNING OUR AGE) across from a full-page photo of a matron arguing with a baseball umpire (MOM GETS THUMB); nine color pages of Renoir paintings followed by a picture of a roller-skating horse; a cover announcing in the same size type two features: A NEW FOREIGN POLICY , BY JOHN FOSTER DULLES, AND KERIMA: HER MARATHON KISS IS A MOVIE SENSATION. Somehow these scramblings together seem to work all one way, degrading the serious rather than elevating the frivolous . . . [T]hat roller-skating horse comes along, and the final impression is that both Renoir and the horse were talented. (pp. 11-12)

But is it truly Masscult? Or was the Life tongue here merely inside the Life cheek?

The examples described above are actually from an issue of Life from May 1952, back in the days when Life was mostly a showcase of black-and-white Rolleiflex photography. By the early 1960s it was mostly color, overly jolly, and difficult to mistake as anything but full-blown farce. Life liked to mock its “serious” features by juxtaposing a silly visual with a deeply solemn headline. For a series on “Democracy Around the World” in 1960, Life showed us the Speaker of the House of Ghana wearing a full-bottomed horsehair wig, with the headline “GHANA’S LEAP FROM STONE AGE TO EAGER NEW NATIONHOOD.” During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis we got a cover of a smug Jackie Gleason while his wife (a scantily clad showgirl) poses underneath a headline for grim forebodings BY CLARE BOOTHE LUCE (“CUBA: Let’s Have the Whole Truth”). The unspeakable deformities from THE DRUG THALIDOMIDE appear to be illustrated by a gleeful Janet Leigh wearing a stack of seven or eight Shriner fezzes.

This is not Masscult at all, then, but rather Macdonald’s old specialty: college humor, spoofing the solemn and the pompous. He slipped up badly when he relegated Life‘s juxtaposition of Bertrand Russell and the rollerskating horse to the depths of Masscult.

Which brings us back to Tom Wolfe, who by rights was Macdonald’s successor in the grand tradition of pomposity-lancing. Too much alike, and inevitably they came to lows. This first happened in the mid-1960s, when Wolfe was writing for the New York Herald-Tribune’s Sunday supplement, a little rag called New York, edited by onetime Esquire editor Clay Felker.

Wolfe wrote a pair of hyperbolic, cruelly speculative, takedowns of The New Yorker, the first of which was called “Tiny Mummies! The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead.” The New Yorker‘s editor William Shawn wrote Tribune owner John Hay Whitney, demanding that he spike this blasphemous piece. But as the Tribune was then on its last legs financially, Whitney and Felker figured they had nothing to lose. So the article ran, and — ZOOM! — became perhaps Tom Wolfe’s first really big attention-getter, at least in the Sunday supplement calling itself New York. It was 1965. And it didn’t really matter that the Herald-Tribune went under a year or two later, because Felker and Wolfe and their merry band of New Journalists regrouped and relaunched New York as a standalone weekly magazine that soon earned more money every year than the Herald-Tribune ever made (or lost?) in its dotage.

Thus ensued the most elegant, hilarious literary feud of the era. Macdonald answered Wolfe’s attacks on The New Yorker with two long essays in The New York Review of Books (together, rather longer than Wolfe’s original articles) and denounced his style of writing as “parajournalism,” the para- meaning parody. Wolfe was absolutely delighted, and wrote a letter to the editor, calling Macdonald “that testy but lovable old Boswell who annotates my laundry slips. Please print this letter up front so that he can respond at length . . .”[2]

You can buy Tito Perdue’s Materials for All Future Historians here.

In his marvelous introduction to this 2011 edition of Masscult and Midcult (etc.), Louis Menand notes that there was a very good reason why Wolfe got under Macdonald’s skin this way. Macdonald was the decrier of Kitsch, of mass entertainment, of lowlife culture. And here was Wolfe, actually celebrating those things Macdonald at least pretended ritually to abhor:

custom cars, beehive hairdos, Las Vegas signage, rock-‘n’-roll dance styles, and so on. This was territory that Macdonald and his generation of literary intellectuals had marked out as beneath critical consideration — and here was a journalist, with a doctorate from Yale, who had written a best-seller about the stuff.[3]

Finding his way on his own, unhobbled by any need to pander to faddish theory or Frankfurt School obscurantism, Wolfe was basically doing the same thing Macdonald did, or thought he was doing: being an honest critic, describing (or making fun of) what was in front of his nose — as George Orwell would say. The moral to all this, it seems to me, is: Don’t overthink things! Don’t be like Dwight Macdonald! Be like Tom Wolfe — or George Orwell! Tell us about bawdy cartoon postcards or topless dancers, and don’t go scratching around for obscure Marxian or structuralist lessons. Often enough, things mean just what it looks like they mean.

That was a plan Orwell himself consciously followed most of the time, and when he got tiresome and went off the rails, it’s usually because he was pulling a Macdonald, injecting Marxian cant for the benefit of Partisan Review (PR) types. In fact, the “off the rails” instance that sticks in my mind is an essay Orwell did for PR in July 1947, “Toward European Unity,” in which he parrots some gawd-awful commonplaces about the United States and “capitalism” that look to have come from the mouth of Molotov.[4]

They were good friends, Macdonald and Orwell. As tight as friends can be when they’re 3,000 miles apart, not in precise agreement politically, and never actually get to meet in person because one suddenly chokes to death from a hemorrhaged lung before that meeting could ever happen. It’s a friendship that’s usually scanted or overlooked entirely in Orwell biographies. Yet, Orwell’s “London Letters” in Partisan Review between 1941 and 1946 were written largely at Macdonald’s behest, and when Macdonald left PR to found his own journal, Politics, in 1944, he urged Orwell to contribute. Orwell’s first appearance in Politics was the famous essay on detective stories now usually titled “Raffles and Miss Blandish“; he’d agreed to write for Politics so long as he didn’t have to do any political stuff.

Before moving from Islington to the wind-swept Isle of Jura in 1947, where he intended to finish Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell complained of needing a new pair of stout walking shoes or “boots.” He had very large feet for which it was nearly impossible to find shoes in those post-war days, and shoe leather was scarce, anyway. So now there followed a correspondence in which Macdonald buys Orwell a pair of walking shoes so sturdy “you could walk to Scotland in them” — size 12 as Orwell requested. Macdonald scuffs them up and proposes to package them with old sweaters with the label “old clothes,” so they don’t get backed up at Customs . . . or stolen. Orwell tells him to send the shoes one at a time, since only a one-legged man would be interested in stealing a single shoe. Macdonald decides to send them together, because what good would it be if one shoe arrived and not the other?

In the end, the shoes turn out to be too small and Orwell lucks into another pair when some other big-footed man at the local shoemaker fails to pick up his order. He sends the Macdonald pair off to Germany, in aid of some other needy soul.

While getting through his tuberculosis convalescence after finishing Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell and Macdonald discuss a visit to America, a year or two down the road. Perhaps even a speaking tour? One now knows that such a tour would be a landmark event, something like the speaking tours of Charles Dickens or Mark Twain. The celebrated author of Animal Farm and the recent bestseller Nineteen Eighty-Four! We’re talking 1950, ’51, ’52; so of course it would take on a Cold War coloration, and the tour would be denounced by the Left as a series of anti-Communist rallies — which Lord knows it would become, inevitably, however much those two Men of the Left, Macdonald and Orwell, might protest. Orwell would find himself invited to sit on a dais with General Douglas MacArthur, and Senator Joseph McCarthy would try to arrange things so that Orwell could address a joint session of Congress, just like Churchill in 1941! Orwell would appear on the cover of Time, and a timely Orwell essay would run in Life, alongside an explanatory, unsigned sidebar penned by Whittaker Chambers. This would change our present-day perception of George Orwell enormously. Or maybe it wouldn’t.

Macdonald and Orwell were not on the same wavelength politically, Macdonald forever trying to comprehend current events through the changing prism of his ideology, which remained far more literally Trotskyist and Marxian than Orwell’s; Orwell being sui generis, a non-Marxist, never-Marxist who called himself merely a socialist or “a man of the Left,” because he thought that was the decent place to be. Macdonald read Orwell’s independence as being “dense” politically; meanwhile, “Orwell found Macdonald’s analytical frameworks so rigid that he sometimes was forced to defend indefensible positions.”[5]

Macdonald has often been called the American Orwell, though Orwell is unlikely ever to have been called the English Macdonald. Macdonald never did an Animal Farm or a Nineteen Eighty-Four, and most people would be hard-pressed to name a Dwight Macdonald book today. Orwell probably diagnosed the problem aptly: It was those “analytical frameworks so rigid.” Macdonald sought an ideology that could be written down in columns and rows — today we’d say “laid out in a PowerPoint Presentation” — and readily explained and adhered to. Someone always in search of a system is not inclined to let loose with free-form creativity.

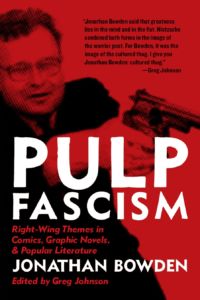

You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Pulp Fascism here.

Beyond that, though, they certainly did have parallels and points in common. Orwell famously went to Eton, as a “Colleger” (i.e., a scholarship boy who lived in the central buildings of the College; that is, one of those for whom Eton College was founded), but later couldn’t go to Oxford with Cyril Connolly and his other friends because he’d screwed around for six years at Eton, hence no scholarships on offer for young Eric Blair. Dwight Macdonald, three years younger, meanwhile went to Phillips Exeter and then Yale, where he mainly screwed around at the soi-disant “Oldest College Daily,” chaired the “Oldest College Humor Magazine,” and supposedly got himself almost expelled for ridiculing a much-honored, jolly old windbag named William Lyon Phelps.[6]

After his school years, Orwell put on a Sam Browne belt and spent five years in Burma as an officer of the Indian police, before ditching it all to become some kind of freelance writer. Macdonald’s initial career post-Yale seems even more unlikely. He didn’t go straight to Harry Luce and Time Inc. Unbelievably, he joined the executive training program at Macy’s department store. A year or so of that may or may not have given him the interest and insight to hop aboard Luce’s next venture, that splendiferous celebration of big business, Fortune magazine. Birthed in late 1929, at the start of the Great Depression, Fortune was aggressively priced at one dollar a copy. Lavish in design and production, it was printed on heavy, coated, cream paper, measured 11″ x 14″ and was perhaps 3/4″ thick. Early issues nowadays go for, well, a fortune.

Orwell published far more books than Macdonald in the 1930s and ‘40s (Macdonald didn’t publish any, actually, other than a book-length tract against Henry Wallace), yet he also struggled more and frequently put himself at risk. Thus he died in early 1950; near-contemporary Macdonald lived on to 1982. And Macdonald mostly lived in the lap of luxury, relatively speaking, and never had to beg anyone to buy him some sturdy walking shoes. In 1934 he married a wealthy young woman named Nancy Gardiner Rodman, whose brother, (Cary) Selden Rodman (Jr.), was a prolific poet, critic, and champion of primitive folk art.[7]

It was the Rodman money, more than anything else, that enabled Macdonald to get by during his years of editing and writing for Partisan Review and Politics. Surely, between the time he left Fortune in 1936 and whenever exactly he went on staff at The New Yorker in the early 1950s, he never earned enough from his journalism to support himself and his family (two sons; eventually two wives). The rather dilettantish aspect of Macdonald’s oeuvre may well be the result of never having to try too hard, never having the wolf at one’s door, always having the leisure to spin vague castles of Masscult-Midcult ideology in the air.

Notes

[1] A famous, deathless comment on Time‘s Midcultiness occurs in Edward Albee’s early one-scene play, The Zoo Story, about two characters who meet on a park bench and one of them, who proves to be semi-lunatic, gravely accepts a piece of information from Time magazine, because “Well, Time magazine isn’t for blockheads!”

[2] Nearly six decades later, it’s hard to see what the hilarity was all about. As a taste-setter The New Yorker was indeed dead in the water. Tom Wolfe was beating a dead horse, and he knew it, but he and Clay Felker wanted to bring eyeballs and ads to the foundering Trib, so he gleefully embellished all sorts of nonsense. Some of his inventions and hyperboles are virtually inaccessible to the modern reader. For example, Wolfe’s theorizes that New Yorker editor William Shawn was a quirky, retiring fellow because once upon a time, when he was a youngster in 1924 Chicago, he came close to being the victim of Leopold and Loeb’s “perfect murder.” In the end of course they settled on Loeb’s neighbor and cousin, forever afterwards to be known as “fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks,” whom they beat to death and hid in a culvert pipe. Shawn and Franks attended the same secondary school; that’s the only connection between them. Macdonald, infuriated, spends a lot of ink taking Wolfe to task for this. For those interested, his two New York Review of Books articles can be found online.

[3] Introduction by Louis Menand, in Dwight Macdonald, Masscult and Midcult / Essays Against the American Grain. It is not to take anything away from the Macdonald pieces to mention that Menand’s Introduction is the clearest and most entertaining essay in the book.

[4] And probably did, though Orwell wouldn’t have realized it at the time. Molotov and Stalin had just come out against Soviet participation in the Marshall Plan, dismissing it as an American effort to stave off economic depression and “the crisis of capitalism” by expanding its export markets and dumping its surplus goods on Europe. This notion even found its way into Nineteen Eighty-Four, which Orwell was writing at the time, except there the solution to surplus production was continual war rather than new export markets.

[5] David R. Costello, “‘My Kind of Guy’: George Orwell and Dwight Macdonald, 1941-49,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 40, No. 1, January 2005.

[6] The story is almost certainly an exaggeration that Macdonald liked to tell on himself. In one version, he was about to publish an opinion column in the Yale Daily News, stating that “Billy” Phelps was too incompetent to be teaching Shakespeare; however, the Dean learned about this and stopped him. In another rendition, the college newspaper rejected the piece, whereupon Macdonald proposed to print it up as denunciatory leaflets and distribute it all over campus. This would have happened in or about that year of wonderful nonsense, 1927.

[7] While at Yale in the early 1930s, Selden Rodman founded an ambitious, iconoclastic little magazine called The Harkness Hoot. The Hoot initially drew national attention for its mockery of Yale’s ceaseless building of neo-Gothic structures. Frank Lloyd Wright congratulated the magazine for its bold strike in favor of modern architecture, and asked Rodman and company to send a stack of copies to the University of Wisconsin (his alma mater). Later on, before it folded in 1934, the Hoot published an on-the-ground report from the “new Germany,” including a description of prison camps and an explanation of why political prisoners were being rounded up. “What would have happened if you didn’t imprison these Communists?” the young reporter asks, to which the reply comes: “We’d all be dead!” (I seem to recall this report was somehow arranged with the help of young Franz Friedrich von Papen, son of the Vice Chancellor of Germany.) Shortly after this article appeared, a sophomore named S. H. Ireland dropped out of Yale to go to Europe for a while and check out this new Germany. It never occurred to me to ask Wilmot Robertson (for it was he) if he’d been a fan of The Harkness Hoot.